Funny that, while taking a work break after re-reading Kafka’s short story “The Vulture” (“Die Geier”), I should encounter this animal interest piece about a beluga whale caught on tape sounding an awful lot like a person.

Funny that, while taking a work break after re-reading Kafka’s short story “The Vulture” (“Die Geier”), I should encounter this animal interest piece about a beluga whale caught on tape sounding an awful lot like a person.

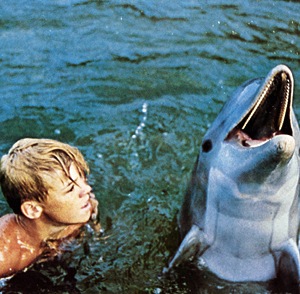

According to i09, “for the first time ever, researchers have presented audio evidence of [whales] spontaneously mimicking human speech,” though marine researchers had long reported rumors that marine mammals seemed to be playing back some of their own speech patterns underwater. Eerily enough, it took researchers a while to figure out it was the beluga “talking” when they seemed to hear far-off voices: a diver, who had been in the tank with the whale, surfaced and asked “Who told me to get out?” His colleagues eventually concluded that the “‘out’ which was repeated several times” came from the whale.

Uncanny, right? A whale talking like a person tells you to get the heck OUT. Eerie how the whale had been presumably listening to, and even maybe understanding, human speech for long before researchers realized. Though, admittedly, the audio recording is pretty unthreatening and adorable; it sounds like someone gave a giddy ten-year-old a kazoo.

“The Vulture” has its own uncanny animal whom you don’t expect to understand human speech. The story is about a man whose feet are being hacked at by a vulture. When a gentleman passes by and asks the man why he doesn’t fight the vulture off, the man explains he’s worried the bird will just go for his face. The gentleman offers to go home and get his gun. Here’s the narrator:

“During the conversation [between the man and the gentleman] the vulture had been calmly listening, letting its eye rove… Now I realized that it had understood everything; it took wing, leaned far back… then, like a javelin thrower, thrust its beak through my mouth, deep into me. Falling back, I was relieved to feel him drowning irretrievably in my blood, which was filling every depth, flooding every shore.”

Some fun parallels (yes, I have a twisted sense of fun): not just does the vulture listen and understand, but like the beluga he also mimics human behavior — leaping forward to murder the man before the man can murder him. Plus, we’ve got water imagery any self-respecting whale would appreciate: blood that drowns, blood that floods, blood that fills up shores. What’s creepy in both cases is that a creature we think we’ve got figured out has in fact figured us out. The next time house guests joke about eating my pet rabbit, I’m going to warn them she might go for the jugular.